Trauma has been in the news lately. We just passed the 6-month anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombing, the one-year anniversary of the mass shooting in Aurora, and ongoing coverage of returning veterans facing PTSD, so there has been extensive coverage about victims, survivors, and bystanders throughout the news. One story, on WBUR, featured six nurses who provided triage care to victims immediately after the bombing. After the bombing, they decided to get matching tattoos to memorialize the victims and honor their experiences. One of the nurses noted, āBeing there together has been a great support. Weāre able to talk with each other when something upsets us, something that even close family members canāt really understand,ā

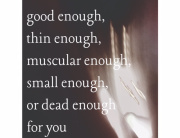

Her statement rang so true to me as a survivor of sexual violence. Community and solidarity with other survivors is an important part of healing and recovery, yet sexual abuse and assault are designed to make victims feel alone.Ā But survivors of sexual violence need the same thing that veterans and other kinds of trauma victims need in order to heal:

- Grounding in the reality of the traumatic event that took place. No one doubts that the marathon bombing actually happened or that a battle took place.

- To be seen, heard, and believed. No one questions whether a veteran or a witness is telling the truth about what they saw and how it impacted them. We listen to stories about traumatic events to create a shared narrative that helps us heal.

- Spaces of acceptance, honor, and healing. Victims and survivors come together to share their experiences, understand their trauma more deeply, and support each other on pathways to healing. Through vigils, memorials, walks, and community gatherings, we create spaces for healing and recovery. We honor the trauma that took place, and the courage it took to survive it.

- A community of support. Friends, family members, and the community rally around survivors and express outrage over what they experienced. Bystanders and witnesses are as deeply engaged as victims and survivors. For veterans, those who escape war without deep emotional wounds stand in solidarity with those who are not so lucky.

Ā

Public traumas like war and terrorism allow survivors to process their trauma more publicly. We understand and accept that they may experience a range of emotions, and make space for those feelings and reactions. We remember their trauma together as a community, honor them for surviving, and try our best to help them heal.

Ā

As a survivor of sexual violence, the first experience of community can be profound. For some, they are lucky to experience support in the immediate wake of an assault. Many suffer in shame and silence ā or worse, are greeted with disbelief and anger. During my freshman year of college, I participated in my first therapy group specifically for survivors of sexual violence. As part of the group, each member shared their personal story with the other members through a guided, facilitated process. It was among the most sacred and powerful experiences of my life. I was forever changed by the solidarity I felt with the group members who honored me with their experiences.

Ā

Itās my hope that all survivors can find solidarity with each other, and find ways to be supported and healed by their communities. There is no amount of candlelight or rallying that will ever make sexual violence OK, but we can collectively ensure that survivors donāt continue to suffer alone when most of us are standing by to support.

Ā

Ā