As someone who was sexually abused by both men and women and who has very close relationships with male survivors of sexual violence, I am both fascinated and troubled by the themes about gender and sexual violence in traditional media, blogs, and general conversation. All too often, sexual violence is viewed as something that takes place between men and women not something that impacts men and women alike.

First and foremost, we’re stuck on the term rape, which is still a very gendered term. Until last year, thefederal definition of rape only covered the forcible penetration of a man’s penis in a woman’s vagina. So when we talk about rape – the Steubenville rape, the gang rape in India, or even the rape problem in general – it evokes male perpetrators and female victims. Rape leaves out other forms of sexual violence that are equally troubling, like child sexual abuse, fondling, or being forced to engage in sexual behavior against one’s will.

The overuse of the word rape and the gendered associations that go along with it leads us to conclude one of two things:

- Rape is a women’s issue because women get raped. This comes in many forms: Don’t get drunk. Don’t sleep around. Take Back the Night. Cover your drink. Women are under attack, so learn how to fight back. Travel in packs. Don’t be alone at night. Wear rape prevention underwear.

- Rape is a men’s issue because men are the rapists. We need to stop raising our sons to be rapists. Men get away with rape. Men should stop raping women. Men rape women because they are men. There was even a recent meme that turned rape prevention tips on its head, but it was still all about men raping women.

Some of these perspectives are subtle. Others are overt. Both of them are actually mis-informed. Here are some facts that can’t be disputed:

- Men and women are both survivors of sexual violence.

- Men and women are both perpetrators of sexual violence.

- Men and women are both bystanders of sexual violence.

Sure, we can argue about who gets assaulted more frequently or more severely. We can talk about how who commits a larger percentage of certain types of sexual violence. We can talk about how sexual violence impacts some worse than others. It’s a lot easier to discuss, debate, and become irate about these differences (some of which are important), rather than focusing on how a gendered conversation shuts out the potential to work together to call an end to all types of sexual violence.

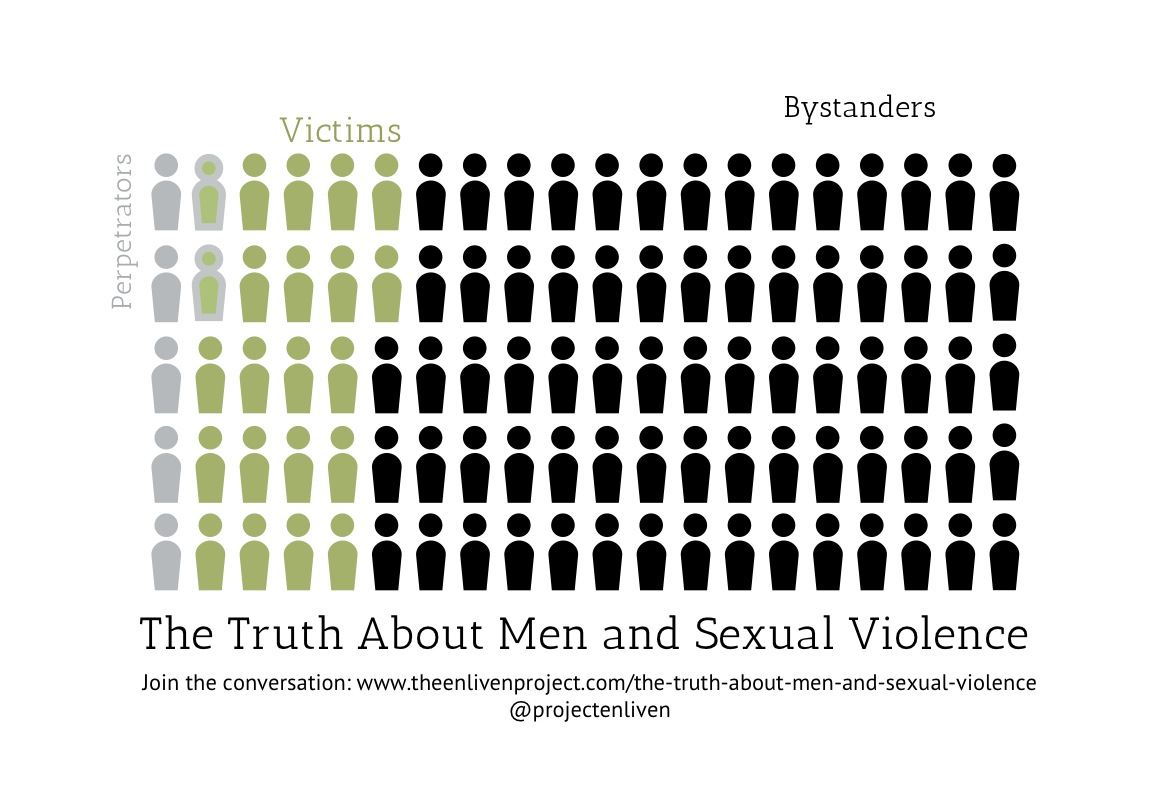

I founded The Enliven Project to begin breaking down these myths, and creating new ways to engage in dialogue about sexual violence. Today, we are releasing The Truth About Men and Sexual Violence convo-graphic to spark discussion about the ways in which men are—and aren’t—impacted by sexual violence. (You can read about the data behind it here.) This convo-graphic is designed to drive home two important points:

1. The average man is NOT a rapist. In a room of 100 men, you are more likely to run into a male victim than you are a male perpetrator. The most recent study on male perpetration found that in a group of 1882 men, 6.5% of men self-identified as rapists. This group of 120 men committed 1,225 acts of interpersonal violence, including 483 acts of rape. This means that there are far fewer perpetrators than victims. There are multiple other studies that confirm that most sexual perpetrators are serial perpetrators, many of which are listed inDavid Lisak’s paper.

There has been a lot of discussion of the accidental rapist or the nice guy rapist—the person who just doesn’t know enough about consent and rapes without being aware of it. With this line of thinking, we may assume that while Pete is leaving a party this week with an obviously drunk girl (gender deliberate here to illustrate myth), it might be Ben or Steve or John next week. Why speak up if we assume it’s the norm?

What Lisak’s research suggests is that it’s Pete this week, and Pete next week too. And maybe the week after that too. We can argue about whether Pete is a nice guy who doesn’t know about consent or whether he is a sociopathic predator, but I’d like to think that a better focus is on the majority of people—men and women—who stand by and see behavior like this without stepping in.

2. Men are victims of sexual violence. According to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Study, 22% of men have experienced some form of sexual violence. Some studies suggest the number is a little lower or higher, depending on how sexual violence is defined. But the truth is that men are impacted by sexual violence because they are victims, not just because they are perpetrators. This ought to be a central discussion, not an afterthought.

Male survivors of sexual violence face an overwhelming amount of shame and stigma as a result of our gender lens on rape. Because of that, they are less likely to report, less likely to seek help, and less likely to speak about their experiences.

At its core, sexual violence is not a men’s issue OR a women’s issue. It’s a community issue. It’s a public health issue. It’s an economic issue. It’s a human issue. We need to create space for conversations about sexual violence that allow men and women to bring their whole selves. Everyone feels vulnerable when talking about sex, let alone sex and consent. If we are all worrying about saying the wrong thing, we might not say anything at all. And then the silence continues. The shame continues. And men and women suffer equally.

The remaining men in the graphic are labeled as bystanders. I’d like to think that these 72 men believe that sexual violence is horrific whether it happens to men or to women, and whether men or women commit the crimes. All humans have a fight or flight instinct when it comes to scary and horrible things. We freeze instead of offering a hand. We look the other way. My hope is that more men and women will stop standing by, and start speaking up and standing up for both male and female victims.

Just last week, a male friend reached out to me. He wanted to better understand consent, and the ways in which he could be more responsible in his sexual relationships. He told me that he contacted me for three reasons: I was candid about my own experiences, I was intellectual, rather than emotional, and I was open to his perspectives, even if I thought they were wrong. I believe there are millions of more men and women like him who are hungry for substantive, non-judgmental conversation about sexual violence. Like my friend, they are tired of standing by, but don’t know what to do.

At The Enliven Project, we are committed to a country where men AND women can speak the truth about how sexual violence has impacted their lives and communities. We believe this is the only way that survivors can seek the justice and healing they need to reach their full potential. You don’t need to be a survivor to care about sexual violence—you just need to be a human who wants to learn more. Let’s work together to create a space for deeper conversations, which is the only way that real change will take place.

To learn more about the data behind this ConvoGraphic, please click here.

This post originally appeared on The Good Men Project.

You said something that I want to believe, but I do not see it clearly supported in the studies you reference.

“In a room of 100 men, you are more likely to run into a male victim than you are a male perpetrator”

Of Lisak and Miller’s participants, 6.4% report actions that meet the criteria for rape. We do not know, from this study, how many would meet the criteria for other forms of sexual assault (inclusive of rape).

Within the CDC report, the other sexual violence category, experience by 22.2% of male participants, has a larger criteria for inclusion (p. 19): 1.4% of men are victims of rape, 4.8% are coerced in to penetration, 6.0% are sexually coerced, 11.7% experience unwanted sexual conduct, and 12.8% report (non-contact) unwanted sexual experiences (definitions found on p. 17).

This is all to say, the 6.4% of perpetrators Lisak and Miller report, have explicitly reported committing a rape act. The CDC (and these numbers may be under reported), only identifies 1.4% of men as self-identified victims of rape. Based on these numbers, in a group of 100 people, you are more likely to run into a male perpetrator than a male victim.

In order to substantiate the above quote, you need to compare male perpetrators of sexual violence (however defined) to male victims of sexual violence (defined in the same manner), and I do not believe that can be done with these studies.

I do not mean to, in any way, discourage; only to caution against a statement that reaches beyond the findings of your sources.

[…] Sexual violence impacts both men and women, and relationships along the spectrum of sexual orientations. However, “99% of people who rape are men.” […]

based on a definition specifically gamed to exclude female rapists. It’s likely to be closer to an even mix of men and women, especially given that there are a ton of women out there that don’t think it’s even possible for them to be a rapist.